Chemistry is the key building block of all materials.

“Materials Science” is an interdisciplinary field that includes the discovery, design, and development of new and innovative materials. Materials Science is, essentially, how materials are made. It includes the science that defines the physical and chemical properties of solid materials. Chemistry is the key building block behind all materials.

In the case of building, design, and construction, material scientists rely on architects, designers, and sustainable building professionals to understand their evolving needs. This can include material performance needs, sustainability goals, trends in aesthetics, and endless other inputs.

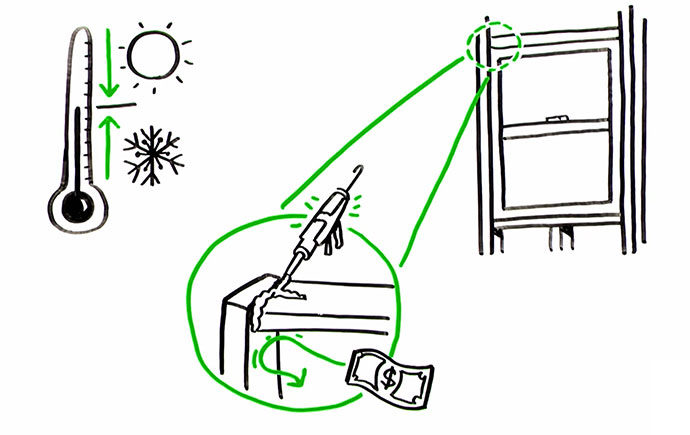

Chemistry plays a crucial role in creating various materials used in buildings, including roofing, wall and floor coverings, as well as countertops.

Hover over and click on the green hexagons to learn more about where the products of chemistry are used in buildings.